A glacier at Pratt Rock

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle May 14, 2019

Robert and Johanna Titus

We were happy to read in the Mountain Eagle of plans for the upcoming restoration of Pratt’s Rock. It’s quite an unusual location; it’s been there a long time and does need an upgrade. We look forward to seeing what will happen, and we hope, when things are done, there will be some appreciation for the geological heritage of this fascinating site.

Had all gone to plan then Zadock Pratt would have had quite the Mausoleum up there, but that did not happen. Nevertheless, Pratt does still have a most impressive monument. Probably most all of you have visited it. Many of you have climbed up and seen closeup the carvings that are there. There is still a chamber where Pratt planned to be buried. Then there is the poignant image of Pratt’s son George who died at the Civil War’s Second Battle of Bull Run.

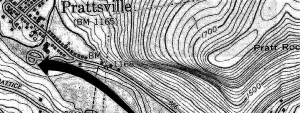

None of this would have or could have been if there had not been such a steep slope there to begin within. Take a look at our first illustration; it shows a topographic map of Pratt’s Rock. Can you “read” contour lines? Then you will recognize the steep Pratt Rock slope from the closely spaced contours. It’s nearly a cliff and it faces the valley of Schoharie Creek which flows through Prattsville. Ledges of Catskill sandstone tower above the valley. A ledge is just a ledge, isn’t it? Well, not where we come from; we are geologists and we know there is a deeper story here

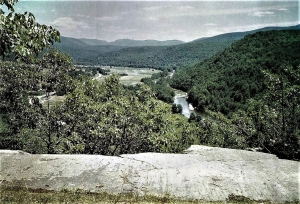

We hike up to the carvings and then continue onwards to a ledge that offers a fine view of the valley. See our second illustration, a photo of that ledge. Notice the smooth surface and the sharp drop-off of the ledge; there is a cliff there. Less obvious, but quite important, are the scratches on that surface. There is a lot of ice age history here. We look and we see what is called the Schoharie Creek glacier passing by. It has flowed south, swelled up to fill the valley and passed across this sandstone. The ice carried a lot of sand with it, mostly concentrated at its dirty bottom. That sand acted as sandpaper and produced the flat surface. There was more, the glacier carried cobbles and boulders along with the sand. They were dragged across this surface and that produced those scratches which geologists call striations. Knowing this, now you can see that they parallel the glacier’s movement down the valley.

What about that cliff? That’s all part of the same story. Glaciers can be sticky. A glacier, when it passes across a mass of rock such as this, forms a tight bond with it. The glacier continues its journey south, it exerts a tug upon that rock. It is quite possible that the tug will break loose a mass of rock and yank it loose. That’s what happened here. There is nothing unusual about this; we geologists see such things frequently. It has a name; we call it glacial plucking. We stand at the top of this cliff, look down the valley and know that somewhere down there is all that missing rock, buried in the floodplain.

Well, the story we have just related, goes a long way to explain how it was that Pratt’s Rock came to be. It started out as an ice age feature. But there is a lot more to this story. Let’s continue next week.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blog at “thecatskillgeologist.com.”

I submit debris flows answer better. Recently many Canadian geologists have begun to shift to watery flood debris flows as a better answer to tightly twisting gouged bedrock rather than a mile thick slab of solid ice. In fact one geologist using a tilt table and glass microspheres demonstrated that when a V-shaped valley is made in the microspheres, and the table tilted, a sudden moment arrives when the valley suddenly flows from end to end almost instantly, and the result moments later is a U-shaped valley. Debris flows on a different scale in California ravines have been filmed which pulse suddenly, several times within minutes, and leave behind U shaped deposits, some with surprisingly flat bottoms where once a V-shaped ravine was.

This is scours and pluck,

Can debris flows create plucks?

Watery debris flows are much more energetic and versatile than ice. They not only produce scours identical to what are attributed to ice, but they tear apart cliff edges and convert them also into debris flows.