What is in limestone?

Windows Through Time; The Register Star

Robert and Johanna Titus

Last week we introduced you to a special type of rock– the fossiliferous limestone. It is largely composed of fossil shells and fragments of fossil shells. We showed you a very fine example of a shelly limestone, something called the Glenerie Limestone. It is exposed in an outcropping along Rte. 9W, south of the bridge at Glenerie. It is simply an extraordinary rock, absolutely packed with marine shellfish fossils. It is so much fun to explore an outcropping like this.

But how was it, exactly, that a pile of broken shells turned into a rock? That’s an important question. But how can we answer it? After all, nobody was there while it was hardening. Nobody saw it happening. And what can you learn from just looking at such a limestone rock anyway? These might seem like tough questions, but let’s tackle them today.

Turns out that there are different ways of looking at a limestone. One way is to make something called a thin section. That is a slice of rock so thin that you can look right through it. But now, still another question, how do you make such a thing?

You start by cutting your piece of limestone in half. Pretty much every geology lab has a rock saw. It has a turning blade that slices right through rock. You cut your rock into two small pieces and then you pick one and grind it down to a smooth shiny surface. And pretty much any geology lab can do that. We put grits onto a large piece of plate glass and grind the rock. When it is smooth enough, we cement it to a small slide of glass. We cut as much as possible off the limestone so that there is a relatively thin sheet of rock cemented to the glass. If this is done right, and it takes practice, you will already be able to see through the rock. But there is more that needs to be done.

In fact, now comes the hard part. We go back to that plate glass, clean it, and sprinkle it with a very fine grit. Then we grind, and grind, and grind. That bit of limestone keeps getting thinner. And, with practice, geologists can make it very thin. Then a sheet of cover glass is cemented onto it and the result is (drum roll) a thin section! You take it to a good microscope and now you can look right into the rock.

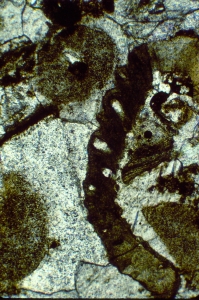

And what you can see is its innards. Take a look at our photo. It shows a thin section view from a piece of Ordovician aged limestone called the Trenton Limestone. One of us (Robert) spent 25 years studying this unit and its fossils. What you see are cross section views of several fossils. On the right center you will see a piece of a creature called a trilobite. We have written about trilobites in Windows Through Time several times. They are marine creatures that might remind you a little of horseshoe crabs. This is a thin section view of one of the creature’s skeletal elements. See the white holes in it? Those housed sensory hairs in life. In the upper left center and lower left there are fragments of crinoid skeletons. Again, we have written about these distant relatives of starfish.

There are several smaller bits of fossil debris in this view. It’s a good image; it shows just how abundant shell fragments are in a limestone. Few of these would be visible to the naked eye so this thin section image is important.

The rest of the view is all white; what is that? It’s cement. It’s a mineral called calcite which is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). That’s the stuff that “glues” all the other grains together to turn the whole thing in a rock.

Calcium carbonate is a very soluble mineral and there is a lot of it in sea water, especially in tropical seas. It readily crystalizes and can quickly, by geological standards, harden a limestone. All those shell fossils are also composed of calcium carbonate and that means that nearly everything you see in this thin section view is CaCO3. Calcite reacts with hydrochloric acid; it effervesces, sometimes very actively. Many geologists carry an eye dropper, filled with this acid, into the field. If they think they have limestone, but are not sure, they just do the “acid test” and see. This acid is marketed as muriatic acid and you can get some and test rocks yourself.

Thin section analysis is hard work, so we don’t recommend that you learn, but we hope you enjoyed reading about it.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”