A Woodstock Ice Age, Pt. 5; the bottom of an old lake

On the rocks – The Woodstock Times, 2008

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

The Comeau, and plans for its development, have generated a lot of discussion in recent months. We don’t live in Woodstock. and it is not our place to voice an opinion, but it is proper for us to describe the geologic history of those 76 acres. And there is a lot of interesting geology there. Let’s focus, today, on some of the ice age history.

If you walk the Comeau trail, almost to its western end, you will find two earthen banks along the Saw Kill. If you know what to look for, there is a lot of ice age history to be seen there. Lots of streams display earth banks; these are formed when stream channel erosion cuts into the side of the riverbank and excavates into the “dirt.” In most cases there is little of great note and even a geologist will walk by without paying much heed, but not here.

If you look carefully, you will find that the earth is layered or stratified. It’s not immediately obvious, but it’s there. Careful examination will reveal more. Some layers, or strata, are light colored and relatively thick. Others are thinner and darker. The thick light layers are made mostly of sand while the thinner strata are mostly clay. This might not sound all that important, but it speaks volumes to the geologist.

Varves

Varves

These horizons of sediment are referred to as “varves.” They are seasonal deposits that form almost only in ice age lakes. Now we are making progress. The sediments here take us back to the end of the Ice Age. At that time, summers were just getting warm enough to melt part of the great glaciers that had filled all of the area’s valleys. The valley of the Saw Kill was emptying of its ice. But, off to the east, there was still a large glacier: the Hudson Valley glacier.

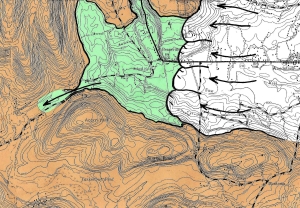

That mass of ice served to dam the lower reaches of the Saw Kill valley and the dam was responsible for something that can be called Glacial Lake Woodstock. When you drive along Tinker Street, just west of the Comeau, you will observe a lot of flat landscape. That’s the floor of the old lake. And the stratified sediments within the Comeau were deposited on that lake floor.

Lake Woodstock, Green

Lake Woodstock, Green

During summers it got warm enough, so the ice melted off of the lake’s surface. Then wind would generate currents within the lake. Those currents swept sand out into the lake and deposited it in the form of those thick, light-colored horizons; we call then “summer varves.”

During winters the lake surface froze over, and there were virtually no currents below the ice. During that time sand could not be moved around and the only deposition that did occur was of very fine, organic rich clays. Hence the origin of the thin, dark “winter varves” that we observe along the Saw Kill.

You can explore the old lake yourself. As we said, you can drive west from the Comeau and observe a lot of flat lake bottom. Bring a map along and you can map the lake bottom and really experience the lake. Some of the flattest lake bottom lies just south of the Saw Kill, across from the Comeau. Most of Bearsville was built on the western end of the lake bottom. Pretty much everywhere south of Tinker Street and west of Woodstock was lake bottom.

An obvious question is “how deep was the lake?” There is an answer to that question, and we will develop the argument for it in a future column. But for now, let’s just say that the lake level was at 880 feet in elevation. But the lake bottom, just across from the Comeau lies at just 600 feet. You do the math; the lake was 280 feet deep!

Drive down Tinker Street and look around at the flat lake bottom; that lake was big. Then look up 280 feet into the air 280 feet; that lake was deep. You have driven down this road so many times and you never guessed this, did you? It rather rearranges your sense of reality. But that is something that knowing a geological history is likely to do from time to time.

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”