Journey to the Center of the Earth, Pt 2

On the Rocks, the Woodstock Times

Nov 12, 1998

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Last week we began a rather remarkable journey into the Earth’s interior. We traveled to the town of Catskill and visited a site that was once possibly miles beneath the surface. We saw beds of stratified rocks there that had been extensively folded by the intense pressures that occur at such depths. But, if a few miles may seem a lot to us, it’s not terribly deep by the standards of the planet. You would have to travel 4,000 miles to get to its center, a mere two or three is hardly anything. So, let’s try to do better this week.

From Woodstock travel across the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge. Head east to Rte. 9 and follow it north to Upper Red Hook. County Rte. 56 takes you east to County. Rte. 55 and that runs along the western shore of Spring Lake. We did some exploring at the north end of the lake and we found some fine outcroppings of a rock type we had not seen before in the Catskill-Hudson Valley region.

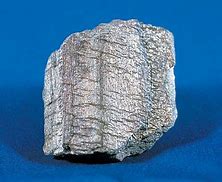

The roadside outcrops are excellent with very good exposures. As you approach these rocks you will observe that they really are unlike anything else in the area. If you have been visiting the sites we have described in our columns, you will have seen nothing like them. Virtually all of the bedrock in the region is stratified sedimentary rock; the beds are bedded sandstones, shales and limestones for the most part. They were once sediment, deposited in sheets that hardened into strata. But at Spring Lake the rocks are not bedded at all. Instead they are composed of shiny, crenulated masses of very dark rock.

The rock is called phyllite. It belongs to a broader category, commonly called metamorphic rock, and it has had a very long and hard history, even by the tough standards set by rocks. The phyllite here didn’t always look like this. A metamorphic rock, as the name implies, has been metamorphosed, changed in its appearance. It was formed originally as something quite different. It may well have been a sandstone or a shale in the very distant past, but it came to be altered. It was buried under very thick sequences of other sedimentary rock, many thousands of feet or even miles of other rock. Then it was caught up in a great mountain building event.

Phyllite

Phyllite

Metamorphism occurs under such circumstances. The rocks are first subjected to the great pressures that are associated with deep burial. Then too, having sunk to great depths within the Earth’s crust, the rocks enter very hot realms and become, quite literally, baked. Combine the effects of high temperature with high pressure and you get metamorphism. The rocks become contorted and crenulated with the pressure. They become shiny as mica minerals begin to grow within them. That new rock is phyllite.

Surprisingly, phyllite is what is called a very low-grade metamorphic rock. That means things could have been much worse. In the deep interior of this enormous planet, even higher temperatures and pressures are encountered and higher grades of metamorphism are found.

If you look at these outcroppings, you will find a number of seams of course, white crystalline minerals. This is quartz and it probably formed here late in the metamorphic history of the rock. The quartz is interesting but not central to our story.

When did all this happen? The answer is probably during the Devonian time period, during what is called the Acadian Mountain building event. That was one of the three big uplifts that led to the creation of what we call the Appalachian Mountain chain. In effect, then, as we travel to Spring Lake, we enter into the deepest interior of the old Appalachians. No, we have not traveled to the center of the Earth, but we have made quite a very good try at it.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”