National Fossil Day

Windows Through Time

Robert and Johanna Titus

Register Star – Oct. 2014

It’s coming up on National Fossil Day once again, and we have put it onto our calendar as something worth observing. But what will be we do to celebrate? We haven’t decided. We can’t put up a Fossil Day tree or carve a fossil pumpkin. We don’t really know what you are supposed to. Maybe we should just go out and do some fossil hunting. It’s, after all, a very nice season to get out and do such things. One of us, Robert, was trained as a professional paleontologist, so he has spent a lot of time doing just that, so, why not this year? National Fossil Day, 2014, is Wednesday, October 15th. It has been organized by the National Park Service in association with the American Geosciences Institute.

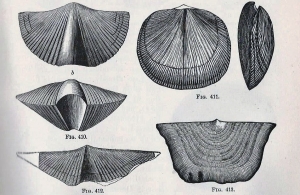

Last year we wrote a column about a very common fossil, a shellfish called a brachiopod. It was a form named Mucrospirifer (lower left in our picture) and it is very commonly found in our local Devonian aged sandstones and shales. Brachiopods, like clams, have two shells, but brachiopods are not mollusks; they belong to a very different group of invertebrate animals. Some species of brachiopods still live in our oceans, but they are quite rare. Back during the Devonian, however, they were enormously commonplace seafloor dwellers.

This year, let’s describe a wholly different type of Devonian animal – the trilobite.

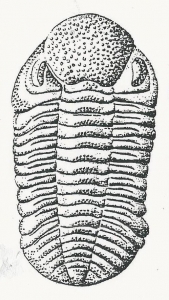

Trilobites belong to a major group of invertebrates called the phylum arthropoda or simply the arthropods. Those are invertebrates that have external skeletons and jointed legs (actually “appendages”). We can‘t think of a better living example of an arthropod than the lobster. They possess very well-developed external skeletons and wonderful jointed appendages.

So too did the trilobites. Their external skeletons were divided up into three lobes – one running down their centers and two lateral lobes as well. That describes their backs, but underneath there was a long series of jointed legs. At the front end was a head which also had three lobes. They are not likely to have been terribly intelligent, but they did have something of a brain in the center of their heads. At the tail end of a trilobite was, of course, a tail! It also had three lobes, but it usually came to a pointed end.

Trilobites lived on sea floors. They date back to the early Cambrian time period which was more than half a billion years ago. They were very humble creatures; often they were scavengers, living by finding things to eat that were just lying on the bottom of the ocean. They were numerically important seafloor dwellers back then. In fact, whenever a geologist thinks about the Cambrian, it is likely with an image of trilobite. Trilobites were important bottom dwellers for several hundred million years, but they never surpassed their Cambrian success. They endured a long very slow and progressive decline. As the eons passed by, they just became less common and less diverse. Their final chapter came at the close of the Permian time period. That was about a quarter of a billion years ago.

Their final extinction is considered the event that brought the Permian Period to an end. We have to think that there was a final day, and a final hour, and a last minute, when the absolutely last trilobite experienced its final heartbeat. At that solemn moment, a great group of animals had disappeared. Extinction is, after all, forever.

But they remain, sort of. They are all dead but their fossils still can be found. Trilobites are among the most coveted and treasured fossil finds that a collector can hope to bring home from a day of hunting. Good ones are, however, very scarce. They had jointed skeletons, and, after death, the processes of decay caused those skeletons to disaggregate and fall apart. Because of that it is not very common for collectors to happen upon a complete and fully articulated skeleton. The two of us have only found a few of them.

The one that we have chosen to illustrate is called Phacops rana. It is named that because paleontologists have decided that it closely resembles a type of frog call Rana. It is a beautiful trilobite and it has been found here in our part of New York State. It was native to the Helderberg Sea and is sometimes, but not commonly, found in the Helderberg Limestone. That’s the unit of rock that makes up the great ledge at John Boyd Thacher State Park. It is the same limestone that you see along Rte. 23 at the large outcrop just west of Catskill. Can you go and find one for yourself? That is VERY unlikely.

Have you found a good fossil trilobite? Send us a picture at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join our facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”