The abyss at Olana June 25, 2020

The Abyss at Olana

Robert and Johanna Titus

But the real tourist attraction in the area is Olana. We stood on the bank in front of the south-facing porch of the old mansion and gazed at its fine view of the Hudson Valley and Catskill Mountain. This is one of the great vantage points from which to see the Catskills. There are days when the atmospheric conditions are just right, and the mountains seem to reach out to you. It’s not just a view; this is also a genuine work of art. Frederic Church intended the porch should have this vista; it is, among many others, one of his “planned views.” For thirty year he was able to enjoy the scene and we envy him that.

But as geologists, we are privileged to see some other views at Olana. On that wonderful site our minds drifted back into deep time. We were at the bottom of the abyss that was once here. The waters were cold and black, but more than anything else they were still and silent. This was a dead seafloor. Nothing crawled across the mud and nothing swam in the waters. We scooped up some of the mud; it was soft and sticky. It was foul with the remains of dead microbes that constantly rained in from above.

With time the avalanches came. The stillness was abruptly interrupted as the seafloor was jolted by seismic shocks. Shortly thereafter great masses of sediment began tumbling down the slopes. For long minutes there was the rush of dirty water. The torrent boiled as murky clouds billowed upwards all around us. Then the current slowed and gradually the water cleared. The Olana seafloor returned to it silent dead, stillness.

Our mind’s eyes rose through tens of thousand of feet of quiet water until they reached the surface of the sea. We gazed eastward and saw dense black clouds rising above the horizon. The blackness drifted my way and soon it rained volcanic dust into the water all around. Then we looked back eastward again and now a rising landmass had replaced the black clouds on the horizon. The stark profile of volcanic mountains defined this new horizon

The passage of time accelerated. As we watched, this landmass grew taller and its shores swelled out toward us. We were soon lifted out of the sea by the rising gray crust. Occasional, the earth beneath us shook with powerful quakes as the land rose higher and higher. Eventually, we found our imaginary selves high atop a still rising Taconic Mountain range. To the north and south, volcanoes erupted in violent spasms. Below, to the west, what was left of that deep sea retreated away from the rising mountains.

There should have been a great deal of green in this image but there was none. This was a fine range of mountains, but it was a dead landscape that had replaced a dead seafloor. We were in the Late Ordovician time period, and life, especially plants, had not yet managed to colonize the lands. All around us was a bleak, blue-gray landscape. There were not even proper soils, just a litter of gray gravel lying upon bare rocks. Only the dry channels of gullies and ravines broke the monotony of the desolation.

We realized that we had come to the very spot where, 450 million year later, Frederic Church would stand. But we were not seeing what he would see. No, below us and stretching off to the west, a large river delta had formed adjacent to the rising Taconic Mountains. A complex of murky streams crossed the dark gray of that delta. Farther away we could see the retreating waters of the sea. It was bleak and lifeless vista, but there was grandeur in this, Olana’s great unplanned. view.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

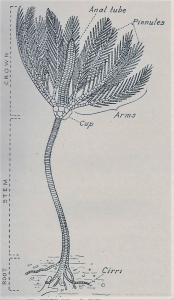

7-13 – Typical crinoid, courtesy NY State Museum

7-13 – Typical crinoid, courtesy NY State Museum Living crinoid.

Living crinoid. 7-14 – Limestone ledge, rich in crinoids

7-14 – Limestone ledge, rich in crinoids