A Roadside Outcropping – 9-26-24

An outcrop near Prattsville

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle; Nov. 8, 2019

Robert and Johanna Titus

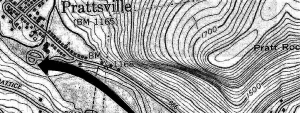

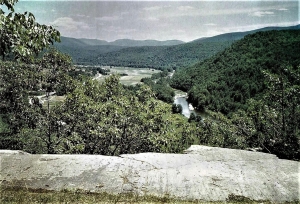

We are guessing that, almost every day, you drive past roadside outcroppings on your routine travels. And we are guessing that you rarely take much notice of them. They are, after all, just rocks. Well, we are in the business of noticing outcrops and sometimes they are quite interesting. We saw one recently on our way home from an event in Prattsville and it was very stimulating. You take Rte. 23 east from Prattsville and turn left where the highway heads toward Windham. Go north about ¾’s of a mile and there it is.

The upper reaches of the strata are fairly run of the mill Catskill sandstones. We didn’t find them all that interesting; it was what we saw below that caught our attention. There, we found about ten feet of poorly stratified, shaley rocks. We are just a little bit uncomfortable in using the word “shaley.” Proper shales are horizontal strata which are also thinly laminated. These were horizontal enough but gently crinkled. Most shales are also usually black or dark gray; these strata were brick red. One of us tugged on his beard; the other furrowed her brow. Both of us were puzzled.

Then it all got worse; at the very bottom of the outcrop the strata were green, not a bright green but a strong enough hue. We could not help but to take special notice of this seemingly out of place color. Green is a rare tint in Catskills strata. But, no matter, red and green it was; there had to be an explanation for these perplexing colors. There was.

Geologists, all around the world look at red strata and reflexively react by uttering the word “terrestrial.” Brick red is the typical color of terrestrial sediments, especially in tropical landscapes. We knew that all these deposits had formed on something called the Catskill Delta. And we also knew that way back then, during the Devonian time period, that delta had lain about 20 degrees south of the Equator in a definitely tropical setting. This outcrop was a partial cross section of that delta, but could we be a little more specific?

We at first wanted to call these red strata paleosols – that word means fossil soils. But we were uncomfortable with that term, fossil soils are usually a good bit more structured than these were. They often display the kinds of A, B and C horizons of typical soils. Ours didn’t, so what was it? Once again beards were tugged, and brows were furrowed. Our final answer involved just the least bit of waffling; we called all this an overbank deposit, not a soil. These fine-grained strata had been deposited as some sort of floodplain sediments and then only just a few soil forming processes began.

All this led to our final story which took us back to a time of drought on the Devonian Catskill Delta. Those floodplain deposits had dried out, exposing them to a lot of oxygen. That oxygen combined with iron to form an iron oxide mineral called hematite which is brick red. That colored the future rocks. But, even during a bad drought, there would still be some water deep in these soils. The water table had been about eight feet deep and down there, without much oxygen, the soils turned green.

So, we have what scientists call a hypothesis to explain what we see along the road. A hypothesis makes sense and is consistent with the evidence. But we are not absolutely sure that we are right and that is why we can’t yet call it a scientific theory. Hypothesis or theory: there is a difference. We don’t know which but still, it is a nice story.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page The Catskill Geologist.”