The Greenport Mastodon

Windows Through time; The Register Star; July 8, 2010

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Our topic today is one of the most notable paleontological discoveries ever made here in our region: the discovery of the first mastodon. This was a big find and was made a long time ago: way back in 1705. That’s when a Dutch colonist found a huge tooth in a bank of clay along eastern bank of the Hudson in Greenport. It weighed almost five pounds, and our Dutchman must have been most impressed. Not so impressed, however, that he was not willing to sell it for a half gill of rum to a local assemblyman.

The tooth worked its way up the political food chain to Lord Cornbury, then Governor of the New York Colony. He sent it off to the Royal Society of London. Today, that would be like sending it to the Smithsonian Institute. The tooth attracted a lot of attention in London, and from just the right people. n 1705 not much was known about prehistoric monsters, in fact very little was known about prehistory. The scientists of the time were puzzled.

There were two hypotheses. Some thought that the tooth belonged to a remarkable beast or fish, but they could not imagine what type of creature it had been. Lord Cornbury and others had another idea; the tooth belonged to a “giant” and they were talking of a biblical giant, referred to in Genesis 6:4. This tooth had belonged to a huge human being!

To his credit Cornbury sent people to search the original site for more skeletal remains and they found parts of a very decomposed skeleton. It was estimated that the beast had been 70 feet long. In fact, they had greatly overestimated the beast, but you can imagine how they reacted to the very notion!

From the very beginning there were others who speculated that the remains belonged to an elephant, but what kind of an elephant and how did such an animal get to the Hudson Valley? For the second part of the question, here again, contemporary religious views offered a solution: the beast had been carried here by Noah’s Flood. That would be difficult to prove, but it was an appealing idea.

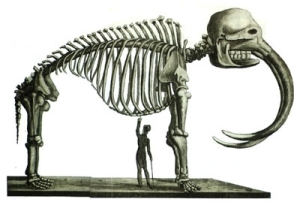

It would take decades to solve the other half of the problem – what kind of elephant had it been – and that came when many more mastodon bones were found in the Ohio River Valley and a complete skeleton was unearthed in New York’s Orange County. Now, at last, scientists could see a whole skeleton with tusks and, clearly, they were those of an elephant, or at least a distant cousin of today’s elephant. But only a distant cousin; now there was a new scientific problem.

The mastodon did not match the Indian or the African elephants; it was a separate and new species. But nobody had ever seen such a creature in the wild. That was still another problem. At this time the very notion of extinction was a new and very troubling concept. Could the mastodon have once lived and then gone extinct? Not many people were comfortable with that thought. Theologians, especially, argued that no such thing could have happened; God would not allow extinction of species he had created. Perhaps not, but if so, where were the living mastodons?

That was a serious scientific question in the early 1800’s and President Thomas Jefferson, a pretty accomplished amateur scientist in his own right, thought he could solve it. The Lewis and Clark expedition was soon to head west, and Jefferson specifically asked its members to be on the lookout for mastodons. Certainly, the animals were extinct here in the east, but perhaps they still lived somewhere out there beyond the Appalachians.

Well, Lewis and Clark found a lot of things all across America, but they never saw and elephant. The results were clear: mastodons were extinct and, like it or not, extinction was something that really could happen – and really had happened.

All this adds up to some very important early progress in the science of paleontology. Our Greenport mastodon was among the very first prehistoric monsters to be discovered. Later generations would find the dinosaurs, but these great mastodons are still quite something to contemplate. All this would lead, with time, to a great understanding of the exotic nature of our planet’s paleontological history; it was one of the first glimpses into life’s distant past.

But equally important was the introduction of the very concept of extinction. We take that for granted today but it was a most remarkable, and disturbing, discovery two centuries ago.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”