The Claverack Giant

The Columbia County Independent

Dec. 20, 2002

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

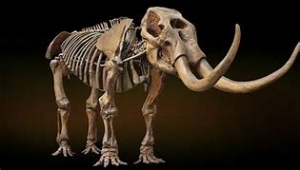

IN RECENT DECADES there has been a small flurry of discoveries of ice age elephants in New York State. You may well have read about the mastodont discovered in Hyde Park; it made quite a stir down there. The bones were found quite by accident in a swampy section of family’s backyard. All they had wanted was to dig a small pond, what they got was an ice age treasure. Researchers from the Paleontological Research Association in Ithaca spent the summer excavating the skeleton and most of it was recovered. Such events are very exciting, and people come from all over to see the bones as they emerge from the muds. Some even got involved in the project, there is never a shortage of local volunteers to help out in such a dig.

Less well known was a similar discovery near Ithaca. Another swampy area yielded the bones of an ice age elephant. This one was a woolly mammoth, and this dig attracted dozens of Cornell students. A big surprise awaited them when, during the excavation, the remains of a second skeleton, this one being another mastodon, came to light. You can imagine the excitement that accompanied this “twofer.”

Such discoveries are always big news stories in the local area. They should be; they are rare and exciting events. But, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries very many more such discoveries were made. In those times it was common for farmers to drain their swamplands and this frequently led to the discovery of large bones. The Hudson Valley of New York State became something of a world capital for mastodonts, as these close relatives of the modern elephants were apparently very common here, especially in Orange County in the lower Hudson Valley.

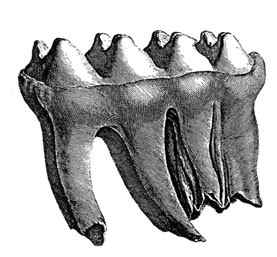

Our story begins in Columbia County. Columbia County is the site of the first discovery of that ice age emblem, the mastodon. This historic event dates back all the way to the year 1705 when a Dutch colonist came across a fossil tooth on the banks of the Hudson River at the town of Claverack, just north of the city of Hudson. The name of our discoverer seems to have been lost to history. It’s a shame as this was, without doubt, the most historic thing that he ever did. The tooth certainly was remarkable. Most of the root had decayed away but the enamel still gleamed. And it was big, weighing in at 4 and three quarters lbs. Evidently, our colonial discoverer thought little enough of it however, as he sold the tooth to assemblyman Peter Van Bruggen for a gill of rum. Van Bruggen brought the tooth to Albany where Edward Hyde, Viscount of Cornbury and governor of the New York Colony, obtained it. Cornbury is most famous for supposedly dressing in women’s clothing, but that is another story altogether. He showed a more scientific side to his nature with his interest in the tooth; he wondered what exactly it represented.

Cornbury wouldn’t keep the specimen to himself; he sent it off to England’s foremost scientific organization, the Royal Society in London. In the letter he sent with it Cornbury reflected upon the various ideas that had been proposed to explain the wondrous fossil. There were two hypotheses: some people thought the tooth to have come from some remarkable beast or fish. Cornbury doubted that; he thought the tooth was human, the remains of an ancient giant.

Cornbury lived long ago in a culture very different from ours. We know what a mastodon is, as we are geologists. You very likely know what a mastodon is as they are very well known to members of our modern culture. All of us are very comfortable with the idea of prehistoric creatures, as we have seen them in the museums, on TV, and in the movies. But, back then nobody, absolutely nobody, had ever even imagined such an animal as a mastodon. Not only had no one ever heard of such a prehistoric monster, but nobody had ever heard of prehistory. That notion would have been quite an unwelcome revelation to Cornbury. He thought, like almost all westerners, that the world was only about six thousand years old, the direct creation, at that time, of God.

So, if there was no prehistory and if there were no prehistoric monsters, then what exactly did Cornbury believe the creature to be? When he used the term “giant” he was referring to the Bible quote “there were giants in those dayes.” To his credit, Cornbury sent men to search the Claverack site for more evidence, and they were successful, sort of. Cornbury’s crew did locate the skeleton and made efforts to dig it up, but the bones were so decayed that they largely disintegrated as the came to the surface. They did estimate the skeleton was 30 feet long. And perhaps, they thought, it had been much bigger than that; a limb bone was found and, before it too disintegrated, it was estimated to have been 17 feet long. A halo of discolored earth surrounded the skeleton, and that was 75 feet long.

Lord Cornbury’s view that this was a biblical giant was enthusiastically embraced by the prominent Puritan minister Cotton Mather, of Witch Trial fame. Mather had once studied to be a physician and had a strong interest in natural history. He, like many ministers of his time, believed that an understanding of nature would confirm the Old Testament account of Earth history. The sediments in which the Claverack giant had been found had been deposited, Mather thought, by the Great Deluge. These views may seem quaint today, but in the 18th century this was legitimate science. The teeth and bones were, Mather argued, the remains of an Antediluvial giant and he wanted to prove that. At that time, he was working on a book to be entitled “Biblia Americana” and in it would be the latest scientific evidence for the Creation and the Deluge. The Claverack giant was important science to Cotton Mather.

But there were other opinions. From the very beginning, in 1705, there were people who had referred to the Claverack teeth as being like the ivory of an “Olivant,” using an old spelling for elephant. The skeleton was not that of a human giant but one of nature’s giants. This was still a very theological view, as the poor creature would have been regarded as having been also a victim of the Deluge. And it must have been quite a flood to have swept a tropical animal so far from its natural setting.

The debate was a long one, and it was not finally settled until a good skeleton turned. Now we have lots of them.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at thecatskillgeologist.com.”