The Poison Sea May 31, 2018

THE POISON SEA – Or Dog days of the Devonian

THE KAATSKILL GEOLOGIST

Kaatskill Life, Summer 1994

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

THE CATSKILLS rarely have a season of “dog days”, the time of hot, humid, heavy, stagnant air. That weather is the lot of more southerly climes. Up here, more often than not, our summers are nearly ideal: warm, dry and pleasant. However, that was not always the case. The rocks contain the record of a very different time in the history of our region, a very long time of perpetually unpleasant summer.

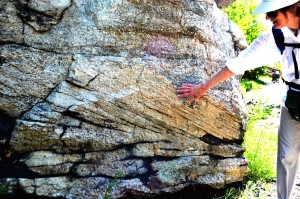

Drive along U.S. Route 20, in the vicinity north of Cherry Valley, and you will see some remarkable strata, the jet-black shales of a unit of rock called the Marcellus Group. All sedimentary rocks represent ancient environments, but it usually takes a while to decipher their

history. The Marcellus communicates its story as soon as it is seen. Its strata are thinly-bedded sedimentary rocks which were once the mud of an ancient ocean’s sea floor.

Robert last visited these rocks late in March with his stratigraphy class. At the time, a late winter snow flurry was approaching. In the cold cloudy sky, the Marcellus is an almost sinister looking sequence of rock: dark, forbidding and mysterious. And that’s exactly what it once was because the Marcellus records the history of the “poison sea” which once covered the western Catskill region.

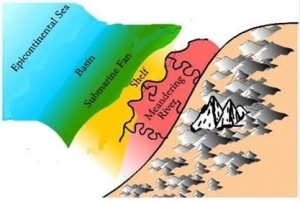

Courtesy of the New York State Museum

It was the geography of the time that made the poison sea. The Catskill vicinity then lay in tropical latitudes so that the climate was quite warm, and so was the ocean. The ancient Acadian Mountains blocked the weather patterns which otherwise would have approached, riding through on the easterly trade winds. That’s the important part. You see, with the weather patterns blocked, there was relatively little wind blowing across the Catskill Sea and thus few currents to churn up that ocean. West of the Acadian Mountains, the sheltered sea became a hot, stagnant “soup”.

We can visit similar seas today. The Black Sea, though not on the equator, is a good example. Being land-locked, weather patterns do not much affect the Black Sea. The waters of such seas are usually stratified. Although the surface waters are very warm, they do contain a lot of oxygen and sea creatures can and do flourish in these shallow waters. It is different below; there bacteria consume all of the oxygen and the sea water becomes anaerobic, making it poisonous for any creatures who may wander in. They don’t; these waters are lifeless.

Such conditions persist right down to the bottom. As is normally the case with oceans, mud accumulates on the sea floor. The mud of oxygen‑poor seas is always jet black in color and, when it is compressed and hardened into rock, it becomes black shales. That’s how the Marcellus black shales formed.

Meanwhile, at the surface of the Catskill Sea, conditions were different. There was plenty of oxygen and a flourishing community of marine life. Masses of floating algae, with many small animals, thrived in a rich planktonic ecology, an oceanic jungle. Today we often call such a marine community a Sargasso.

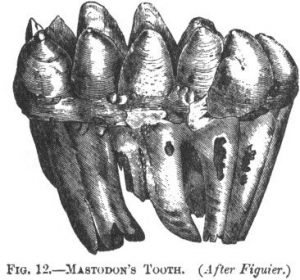

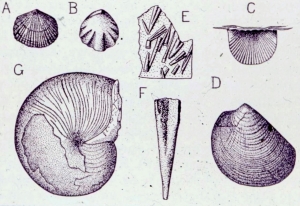

Floating creatures seldom have skeletons and so they are rarely preserved as fossils. Consequently the Marcellus shales display only a few fossils for the careful hunter to find. Back in the 30’s Winifred Goldring, a paleontologist with the New York State Museum, studied the Marcellus and published some fine illustrations (figure three). Among her specimens, three (A, B and C) are tiny shellfish called brachiopods (brachs for short). Brachs will remind you of clams but they aren’t; they are an entirely separate group of shellfish. One specimen (D) is a clam. Notice that brachiopod shells have symmetry and the clam’s shell doesn’t. Pictures E and F are a puzzle. These creatures, called styliolinids, are extinct and we don’t know what they were. That’s a common problem with rocks this old. All of these invertebrates were small and lightweight. They could float in the surface waters of the poison sea, drifting as plankton or attached to floating wood or seaweed. Specimen G is different; it was an active swimmer. We call it a nautiloid and its descendants are still alive. The chambered nautilus, of the south Pacific, is today’s living nautiloid. Closely related to squids and octopods, the nautiloids had tentacles and well-developed eyes. They were active predators, swimming in the surface waters of the poison seas.

You can visit the shales of the poison sea yourself. From Cherry Valley, take county Rt. 166 northeast to Rt.20. Head west on 20 about half a mile and look for the shales on the north side of the road. You can see a better exposure if you head east on Rt. 20 and travel 2.6 miles, where you will reach Chestnut Street. There you will find an outcrop with two units of shale separated by about five feet of gray limestone.

If you patiently pick through the shales, you will certainly find many styliolinids; watch carefully as they are very small. With luck you may find some of the other fossils as well. I have seen some very fine fossil snails below the limestone at the eastern outcrop. That limestone can also be a lot of fun too. This unit represented a temporary break from the poison sea conditions. For a period of time a shallow, oxygenated, tropical sea prevailed here. The limestone has a number of fossils in it, typical of such seas.

The poison seas are misnamed; there were never any active toxins in them, just an absence of oxygen. Nature does that from time to time. The lesson we learn from the poison seas is not that nature creates inhospitable environments, but that she allows life enough time to adapt to her conditions. The planktonic creatures of the Marcellus black shales thrived just a few feet above one of nature’s most inhospitable environments.

* * *

Visiting the Marcellus shales is not the same as seeing the poison sea itself. To do that, pick one of those hot, humid but clear summer days and, in the stillness of the early evening, find a vantage point looking down upon the valley of the Mohawk. The Chestnut Street site may do. From here you can still see the entire expanse of the old poison sea, stretching from the eastern to the western horizons. You are a little above the old sea level, and the atmosphere is just as it was back then.

The summer sun is setting in the northwest and, as it approaches the horizon, the valley of the Mohawk darkens and flattens into a land of somber colors. The fields become a brownish, algae green; the forests turn jet black. To the northwest, the horizon becomes the image of a very still sea. Back to the east there is a distant bank of clouds. As this eastern horizon darkens, those clouds sharpen into the clear vision of the peaks of the ancient Acadian Mountains. Distant mountain ranges often masquerade as clouds, and there is always a shock of surprise when one recognizes the illusion. The lower Acadian slopes are a dark blue brown; they are already in the shade. The jagged pinnacles are small brilliant pyramids; they still reflect the sun.

The air is absolutely still and the surface of the poison sea is as flat as water can be. Gauzy clouds of green algae alternate with bottomless pools of black waters. Occasionally, bubbles of fetid gas rise to the surface and oily dots mar the blackness. Only these betray the suffocating gloom in the depths below. Small, delicate wakes encircle the green; unseen predators are hunting unseen prey. Now a few swells pass heading westward, waves reflected off the distant coast. The green patches lazily drift back and forth in these oceanic breezes. Abruptly there is a disturbance, a quick splash and, for a split second, a mass of tentacles, a single eye and then a brown and white striped shell are seen breaking the water.

Quiet quickly returns as the sun sets and the sea darkens. The evening stars now appear and they seem to be reflected on the glassy sea below. But these reflections gradually blur, and they enlarge into luminous patches of light. Phosphorescent plankton are completing their evening ascent. Their dim glow is all that will light the dark of this Paleozoic sea.

In the growing dark, the image of the poison sea dims. The bioluminescent patches shrink and sharpen into yellow pinpoints of light. Far below, the electric lights of the Mohawk Valley are coming on and now it is they which reflect the stars above. The poison sea is gone, long gone, just an image in the eye and mind of the pensive geologist.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”