Putting You on to a Pedestal

On The Rocks

Robert Titus titusr@hartwick.edu

August 19, 1999

If you live in Woodstock then one of the most accessible of the Catskill hiking trails is the one at Mink Hollow. Head west on Rt. 212 and then, just past Cooper Lake, turn north on Mink Hollow Road. At the end of the road you will find parking and the trail head. Soon you can begin your day on the blue trail. The hike will take you up what was once actually a highway of some importance. Vehicles, loaded with people and goods from as far away as Prattsville traveled on it with destinations in Woodstock and beyond. There are still paved Mink Hollow Roads both north and south, but here in between, the trail stopped being a public road long ago. Today the path takes you up to Mink Hollow itself. That’s a deep, narrow gap in the mountains, mostly cut during the ice age. Beyond Mink Hollow the trail veers off to the northeast and takes you along Roaring Kill to another trail head on Elka Park Road. It’s a nice easy walk in the woods, and that’s nice in the summer. It stops being easy if you want to climb Sugarloaf or Plateau Mountains. Those are tough climbs, but well worth the effort. They are, however, another story for another day.

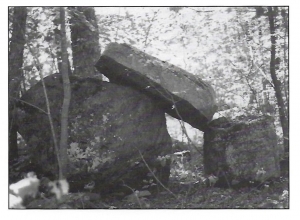

There is one very nice geological feature to see here, however, and that is my subject for today. In Mink Hollow itself there is a lean-to, built to give hikers a place to spend the night. Just south of this lean-to there is a wonderful example of what glacial geologists call pedestal rocks. You can’t miss them. They are immediately east of the trail, just about 100 yards short of the lean-to. They make a most striking feature. There are three good-sized boulders. Two of them are next to each at the bottom of the heap, while the third is a cross bar, lying atop the others and bridging the two.

The Mink Hollow pedestal rock

Just how on earth could such natural Stonehenge happen? First of all, nobody stacked them here; there were never any Druids in the Catskills and the boulders are far too large and isolated for any other people to have bothered with them. Nature did this, and geologists long ago figured out how. Our story takes us back to the end of the ice age. At that time, probably about 16,000 years ago, there was a large glacier, filling all of the Schoharie Creek Valley to the north. A large tongue of that glacier poked through Mink Hollow, and pushed on a short distance to the south.

This was a dynamic tongue of ice and it was actively advancing through Mink Hollow. If the leaves are not too thick, you can look upward from the lean-to and see a number of rough ledges on the western slope of Sugarloaf Mountain. These formed when large masses of rock were plucked from the mountain by the moving ice. And that gets us to the heart of our story.

That huge tongue of ice passing through Mink Hollow had a great number of boulders in it. These were routinely being broken loose from the ledges above and carried through the hollow. Most were dragged off to the south by the currents of moving ice and deposited at the south end of the glacier. But eventually the climate warmed and the glaciers began melting. At that time blocks of rock would have been lowered through the melting ice until they made a soft “landing.” As luck would have it, some boulders would land next to each other, while on rarer occasions, a boulder would end up lowered onto one or two others, forming a pedestal. That’s what happened along the Mink Hollow Trail.

Pause here for a moment and imagine Mink Hollow filled with ice. Look around and you will see all the boulders here. Each one was once the baggage of a glacier. It’s a nice story and just one of those many interesting phenomena that remind us of the influence glaciers have had on our landscape. And it is nice not only to appreciate the beauty of a landscape, but to understand it as well.