Joints on the Wall of Manitou

Windows Through Time

Robert and Johanna Titus

Three weeks ago this blog was about the Wall of Manitou. We wrote about its origins but, ever so coyly; we were not very specific in this. The wall is ten miles long, straight as an arrow and that arrow has a compass direction of south-30 degrees west.

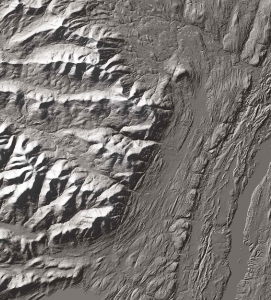

Satellite image of the Wall of Manitou.

And two week ago our blog described long straight fracture patterns called joints. They are very frequent throughout the Catskills and, remarkably, most of the time, they also have compass directions of south–30 degrees west. This was a hint, a big one. Did you pick up on that? There is a story here. Those joint fractures and the Wall of Manitou have too much in common for it to be an accident. There must be some sort of a relationship. Well, there is.

We hope you remember that joints form when great masses of rock are compressed, usually during great mountain building events. The compression does not actually fracture the rock, that happens later in time, when the stress ends and the rocks “relax.” Our Catskills joints compressed sometime after 400 million years ago. Something you would likely call Europe had collided with North America and that collision resulted in the rising of mountain ranges throughout all of New England. Geologists call them the Acadian Mountains. If you keep reading this blog you will hear a lot more about these mountains. Anyway, that massive collision compressed rocks throughout New York State, especially the Catskills

The collision of “Europe” with North America and the resulting Acadian Mountains. See NE/SW orientation.

A long time after the uplift of these mountains, Europe broke free from North America and drifted back off to the east, leaving a growing Atlantic Ocean behind. That split was about 200 million years ago. And that was when all the relaxation occurred and that is also when all those joint fractures came into existence. Joints always form perpendicular to the maximum relaxation stresses. These maximum stresses, as it happened, were northwest to southeast. So the joints formed northeast to southwest, just what we see (We are ignoring secondary joints at a 90 degree angle to the primary ones).

Did you follow all that? Europe collided with North America, compressed North American rocks and, when Europe drifted away to the southeast, all those joints formed. Well, what does any of this have to do with the Wall of Manitou?

It has, in fact, everything to do with it. Perhaps you might like to hike the Blue Trail, north from North Lake. Along the way, here and there, you will find northeast/southwest trending joints. There are a lot of them.

Hikers stand upon Blue Trail joints.

It must have been just like that during the Ice Age. During parts of the Ice Age the Hudson Valley was filled with ice, right to the top. And that ice was moving. It formed a great stream of ice, ever so slowly flowing down the valley, and of course, rubbing up against the Catskill Front.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Ice, when in tight contact with bedrock, forms a bond with the rock. In simple terms, the ice sticks to the rock. Did you ever stick your tongue to the bottom of an ice tray when you were a kid? Well, then you know exactly how sticky ice can be. That happened to bedrock along the Wall of Manitou, during much of the Ice Age.

Well, when enough of a tug was generated, the moving ice would, from time to time, yank huge masses of rock loose. And – you guessed it – those joint fractures proved to be weak points where the breaks could most easily occur. Had you been to North Lake way back then, you would have heard, sporadically, great echoing cracking sounds. Each would mark the breaking of a mass of rock off of the growing Wall of Manitou. Almost always, those fractures had a northeast to southwest orientation.

Over long periods of time – and this is geology; we always have long periods of time – the Wall of Manitou came to be shaped and steepened into what it is today. All the action was occurring out of sight, beneath the surface of the Hudson Valley glacier. Today, the great Wall rises about 2000 feet above the floor of the valley. And it does something that most slopes don’t do. It steepens toward the top. That’s one good reason why it is such a scenic feature.

When we stand at the edge of the Catskill Mountain House ledge, we always look out at the valley before us and we always see it filled to the top by a glacier. The ice slowly moves by us, headed south. And every so often, we do hear those ear splitting cracks, generated by masses of rock breaking free and being dragged off by the advancing glacier. Then our mind’s eyes watch as the ice begins to melt away. The ice shrinks away from the ledge and reveals nature’s ice age handiwork. That Wall of Manitou rises out of the melting glacier. It is a marvelous revelation.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”