A red sunset

Windows Through Time

Register Star

Johanna and Robert Titus

June 4, 2014

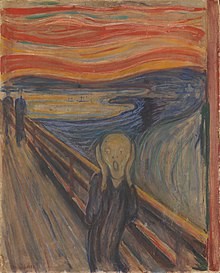

We are guessing you have seen an image of “The Scream,” a very famous and much stolen painting by Norwegian impressionist artist Edvard Munch. There were actually four versions, painted between 1893 and 1910. Our favorite is the 1895 one. It’s the contorted face that catches everyone’s attention. Right behind this unhappy figure is a dock jutting out into a Norwegian fjord with a sailing ship in the distance. But, if you have an alert eye, there is the background; it’s the sky that’s interesting. Munch paints a striking vision of horizons of orange sky, mixed with thinner levels of blue and yellow. Once you take note of it, the sky is just as alarming as the rest of the painting. It’s truly great impressionist art.

We have been frequently guilty of slipping art into our columns, but how on earth have we managed to get Munch’s painting in here? The answer involves some of the professional debate that has swirled for decades over the colorful sky in the scream paintings. Many art historians have argued that Munch had experienced the orange sunsets that occurred all around the world for months after the eruption of the south Pacific volcano Krakatoa in 1883. Volcanic ash erupted from the volcano, drifted high into the sky and circulated around the world. Sunsets were a brilliant orange for quite some time and any number of landscape artists painted them.

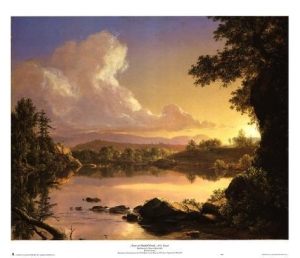

That gets us back to some work done by famed artists Thomas Cole and Frederic Church. Cole was the master painter of the Hudson River School of landscape art. Frederic Church became his student in 1844 and 1845. He would follow in Cole’s footsteps and ascend to be the most successful member of the Hudson River School.

The Thomas Cole house mounts an art exhibit every summer; we never miss one This year’s (2014) paintings were almost all done during, or soon after, the two years of Church’s residency in Catskill. But we noticed something about the paintings done from 1847 to 1849. Those images were far more likely to have bright red sunsets (or sunrises) than others done earlier or later. Church found inspiration in the rising and falling sun. Sometimes it shined right up onto the undersides of the clouds. At other times descending lobes of clouds could be painted in fiery reds while other parts of those same clouds, hidden from the sunlight, would be painted in a variety of dark grays. Interspersed, would be occasional horizons of blue. This gave Church an interesting visual theme to explore. This play of light and color in landscape art is called luminism.

We are including several paintings from the exhibit. First, we ask you to take a good look at Morning, Looking East over the Hudson Valley from the Catskill Mountains, 1848. It has the rich play of colors we are talking about. Also, take a good look at Scene on Catskill Creek, 1847. Although not as red, it shows a brilliant setting sun. Now, look at Church’s Above the clouds at sunrise, 1849. We see, once again, the same play of colors.

We were familiar with the debate about The Scream and we began to wonder about Frederic Church’s paintings. Why did he paint such vivid skies from 1847 to 1849? Was it just his artistic imagination at work or was there something else? We are not art historians; we are practicing geologists. As such, could we find interesting scientific insights to help understand these paintings? We went to work. Scientists follow the scientific method. First, we find problems that need solving; then we develop hypotheses that might offer solutions to these problems. Let’s call our hypothesis “the scream hypothesis;” we argue that bright orange and red landscape paintings are associated with great volcanic eruptions. Scientists “test” their hypotheses by making observations, finding the facts behind them. We looked at history.

We found that there were five eruptions during 1846, four of them in November alone. In May the volcano Tangkuban Perahu, in Java, erupted. Then, in November, there were eruptions in Chile and Japan, then two more in the Cascade Mountains of our Pacific Northwest: Mt. Baker and Mt St. Helens.

All in all, it appears that as the year 1847 began, there must have been a lot of volcanic ash in the skies and they were likely spreading all over the globe. So, our hypothesis is that Frederic Church was influenced by volcanic ash in the skies when he was painting at that time. That hypothesis looks very plausible.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.: