A Big Geology Fan

The Woodstock Times

July 17, 1997

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Striebel Road is one of the those out of the way lanes that you tend not to notice. It’s near Woodstock, but you hardly ever travel upon it. It doesn’t go anywhere in particular and, if you don’t happen to be visiting anyone there, you are not likely to use it. Unless you are a geologist; you see, we like to prowl around everywhere. We look for things. Recently we turned off of the Glasco Pike and onto Striebel Road, and, indeed, we found something.

We rode south on Striebel directly above Rt. 212, which itself runs immediately above the Saw Kill. we found that the landscape to our left was a nondescript plateau, flat and undistinguished. But, to our right, came quite a surprise. Just beyond the road the landscape dropped off a real, no-kidding-around, parachute-type cliff. We had been along Rt. 212, many a time, but we had never realized how steep the slope was here. It’s heavily forested and nearly invisible.

Cliffs aren’t all that unusual, but this one bothered us. A steep cliff is normally composed of bedrock, usually only rock can hold a vertical slope. But this one wasn’t a bedrock cliff; it was composed of a boulder-rich, sandy gravel. It was very likely a glacial deposit, but we wondered what kind of glacial debris would form a cliff along the upper Saw Kill. We knew that there was an interesting glacial story here, but what was it?

As we continued along Striebel Road, it gradually began a descent. The slope steepened and soon we had dropped down into Bearsville. We crossed Rte. 212 and turned onto Cooper Lake Road. As we ascended this other out of the way road, we found ourselves repeating what we had just done on the other road, only in reverse. At first our ascent was steep, then it leveled off higher up the road. So, we knew that the valley of the Saw Kill had once had a large glacial deposit in it. The deposit was composed of course-grained materials, largely boulders, cobbles and gravel. The smooth curved surface of the deposit was relatively flat at its top and then steepened down slope. Long after it had formed, the Saw Kill had gone to work on the deposit. The steep narrow valley of the Saw Kill here was eroded through this mysterious deposit. But, again, what was it?

Bearsville fan is dotted

Bearsville fan is dotted

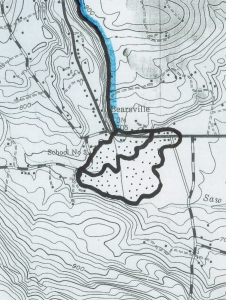

The next thing to do was to study the literature, and that’s where we found our solution. A 1930’s New York State Museum Bulletin mentioned the deposit, and the story, as we had guessed, was a good one. It takes us back about 16,000 years to the time when much of the upper Saw Kill still had a glacier within it. Earlier that glacier had descended Overlook Mountain and flowed down the Beaver Kill valley to Mount Tremper. But now it was melting rapidly; only a small portion of the ice remained. The landscape was just starting to recover from its glaciation and there probably were few, if any, trees in the area. Erosion rates, on the bare soils, were very great. The flow of the Saw Kill, brown or gray with sediment, gushed out of the steep mountains and descended to the valley flats at Bearsville. There the rushing flow slowed down, and enormous heaps of sediment were deposited. We call the deposit an alluvial fan. The Saw Kill flowed across this, probably breaking up into a large number of criss-crossing streams which descended the fan. At the bottom there likely were some substantial ponds. Off to the east, where Woodstock is today, the Saw Kill probably reformed and flowed onwards.

This was a big fan, a mile and a half wide, stretching from Byrdcliffe, in the east, to Bearsville in the south, and then halfway back to Cooper Lake. It originally had the form of a partial hemisphere. It would have been relatively flat on top and then sloped downward, maybe steepening. It must have pretty much filled the valley here; the sediments are about 200 feet deep.

Bearsville must have been a bleak sight at this time with its terrible rush of dirty waters in a barren post-glacial landscape. But this time was limited. As forests returned, they stabilized the earth, the rates of erosion slowed, and the glut of sediment ended. That’s when a more sedate Saw Kill began to erode that alluvial fan and it carved the narrow valley with the steep slopes that caught our attention. It is a good story and just another glimpse into the ancient history of our region.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”